‘Dance your way out of Islam’- China covers atrocities under ‘preventive, educational measures’

After the gruesome beheading of French teacher Samuel Paty by an alleged terrorist, the question is: what we can do about it? How can we deradicalise Islamists and Islamist-friendly individuals? The Chinese government claims to have fashioned a great deradicalisation response. …or have they?

Rise in terrorism and growing obsessions

Over the past few years we have witnessed terrorism and the process of radicalisation constantly evolving. The use of technology, facilitating exchange of intelligence and recruitment techniques, combined with increased migration of people, has enabled terrorism to spread its tentacles across the world (Mythen & Walklate, 2006). Indeed, from the 9/11 atrocity in the US, to the recent beheading of Samuel Paty in France, we see a spread and evolution of radicalisation and acts of terrorism across the world. We appear to be in constant danger and fighting radicalisation and seeking security has become a global obsession.

To tackle incidents, various counter-terrorism and deradicalisation strategies have been applied. China is among the countries that according to its government, has found the perfect deradicalisation tool. Ever since the 9/11 atrocities, the Chinese government has become more focused on strengthening its counterterrorism strategies. Especially after the 2009 clash between the Uyghurs, a Muslim group, and the Han Chinese, these strategies became dominant in the Chinese discourse. They had found their enemy. China’s state media described the incident as ‘an organized, premeditated violent terrorist attack’ and it viewed the Uyghurs as the perpetrators (Truman Center, 2020, par.1). China then focused on controlling and demonising the Uyghurs, who live in the Xinjiang Uughur Autonomous Region (Greitens, Lee and Yazici, 2020). China believed the Uyghurs’ Muslim identity and its geographical proximity to radicalised countries (e.g. Afghanistan) could lead to the group collaborating with international terrorist groups such as Al-Qaeda (Raza, 2019).

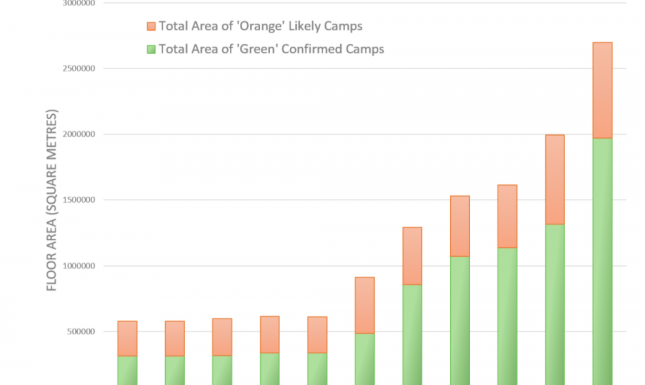

In 2017 the Chinese government enforced the Uyghur Autonomous Region De-radicalization Regulation, to prevent the extremist and terrorist ‘virus’ spreading. They established ‘re-education’ camps across the Xinjiang territory, where suspected would-be terrorists could deradicalise their thoughts. Over the years, some 1 to 3 million people have been put in these camps, for having long beards or owning a Qur’an; detained without trial or verdict. This is contradictory to the Chinese government’s claim that placement in these camps was voluntary. In the meantime, those not yet been detained have been placed under mass surveillance, with QR codes on their homes and facial recognition cameras. It remains uncertain how many camps exist but a new study indicates nearly 400 establishments. These re-education camps ‘are co-located with factory complexes’ which could imply the use of ‘students’ for forced labour (Graham-Harrison, 2020) (see Figure 1).

Effectiveness

Three years after the regulation’s introduction, the Chinese government is happy with its effectiveness. Government officials recently claimed that most - if not all - ‘students’ have now been released. The training the Uyghurs received enabled some 90% of them to find a job and lead a happy life, also combatting poverty. Overall, the regulation’s success in deradicalizing the Uyghurs in Xinjiang has been so great that China is even asking countries hosting Uyghurs to forcibly repatriate them.

China’s claims on the effectiveness of its strategy can be better explained if we understand how it treats religiosity not as an ideology that needs to be deradicalised or ‘fixed’. Rather, it is treated as a disease referred to in medical terms: a virus, a tumour that must be removed from the individual’s brain. Under this rhetoric, re-education is the surgical process through which the tumour is removed. It cannot have any harmful effects because it is a cure, right?

Behind the scenes

Policies like the above have become more dominant in societies in crisis and in the dangerous times we live in. They serve as a real-life illustration of some well-known socio-legal and sociological theories. In particular, what the Chinese authorities describe as a ‘preventive’ non-harmful deradicalisation tactic, is a clear example of politics of denial according to Garland (1996; 2000). The effects of such tactics are evident not only at a local but also an international level. Garland suggests that governments ‘frequently adopt[ed] a punitive “law and order” that seeks to deny conditions which are elsewhere acknowledged and to reassert the state’s power to govern by force of command’ (1996, p.460). To protect the public, the government shows its punitive face by taking peoples’ fears and translating them into a regulation. Often, an emotional dimension is added to the crime by putting the victims in the spotlight. In this way, the public believes the government is listening to their issues and, hence, cares about them. The government also often takes a populist stance, a vital politics-of-denial element, projecting itself as people-oriented, whose sole aim is the protection of the public (Pratt & Clark, 2005). In this way, it continues by brainwashing the public into obedience. This notion relates to Foucault’s (2000) governmentality thesis that the government makes the public obedient by indoctrinating them using discourse that facilitates adherence to its rules.

Public safety made in China

At a local level, the Han Chinese appear to accept the existence of the camps. Though there is not enough evidence to argue that the Chinese public generally defend the work in the camps, a passive ‘being okay with it’ implies the public’s obedience through indoctrination. With the 2009 attack and the recurring state-sponsored media propaganda in the background, they fail to see the Chinese government’s true colours. Under China’s twisted perspective, the strategy is working, isn’t it? As stated above, however, religiosity is not treated as an ideology to be fixed, but as a disease to be removed from the (societal) body. So, their true goal is to eradicate the Uyghurs’ cultural existence, at the very least, and not ‘fix’ them.

The Chinese government aims to demonise the Uyghurs in the public’s mind to such an extent that they might not understand what they are agreeing to. Uyghurs are being dehumanised, turning into the ‘others’ that threaten the well-being of Chinese society. They must be eradicated, like a virus. In the name of the public’s safety, China pre-occupies the public’s mind with their compromised safety. In turn, the public fails to see that the enemy is actually state made. What I mean here is that this enemy is surely the enemy of the state, but not necessarily the enemy of the public too. China’s rationality, as a whole, is based on ‘a new terrorism’ response, where it doesn’t matter if you are a terrorist; what matters is whether a particular authority thinks you could become one (McCullogh &Pickering, 2009). Under that logic, today’s victims could be tomorrow’s suspected terrorists. They just do not see that tomorrow’s threat could be themselves.

Additionally, seeking a security that is merely subjective and partial – meaning that it only applies for some people and sometimes at the expense of others – can expose the public to the threat that it is trying to eradicate. In other words, framing a group of people as being dangerous and/or criminal is likely to produce feelings of resentment and stigmatisation among this group. And because they will start having feelings of not-belonging, it is more likely that they will ‘turn radical’ even though they wouldn’t have done so before this intrusion (Zedner, 2014). Again, the public fails to recognise the issue of the cost and consequence of seeking unneeded protection. Their indoctrination stops them looking beyond the superficial. What they do see, though, is a government that aims to protect the public from the Muslim threat, while helping the Uyghur would-be terrorists deradicalise themselves.

As sweet as it sounds, China has thus far failed to mention that its practices cover up a process of completely erasing Uyghur identity using torture. Former ‘students’ of the camp report experiencing electric shocks, beatings, forced labour, forced abortions for the women and sleep deprivation while in training. Additionally, recent evidence suggests that the campaign has now been expanded to include children though the actual number of detained children is difficult to estimate. Of course, China denies all the above. The Chinese state argues that those camps are nothing more than vocational and educational schools, where students study the law, paint, sing, and dance their way out of extremism.

Can you hear that? It’s China, playing the world’s smallest violin to us.

Security at what cost?

China defends its deradicalisation regulation because it ‘works’, and passionately denies any atrocities taking place in the camps. But the international world opposes the camps and is urging acknowledgement that China is planning a genocide against the Uyghurs. This accusation could lead to grave consequences for China’s trade and political agenda. Recently, a number of unions and NGOs ‘called on major brands like Nike, Adidas, and Amazon to stop sourcing goods from Xinjiang’ (Leali, 2020, par.2). Additionally, the US has moved to establish sanctions to illustrate its disapproval of the Chinese deradicalisation strategy in Xinjiang. Apart from the issues that have arisen because of this strategy, in terms of China’s international political standing, it looks like China has exposed itself to the threat it is trying to eradicate. Remember what was said about China expressing fears of the Uyghurs collaborating with international terrorists, like Al-Qaeda? Well, Al-Qaeda heard that too. Ever since the establishment of those camps, China has received numerous transnational jihadist threats in response to the Uyghurs’ detention. Does that mean that, as Zender (2014) points out, ‘seeking subjective security may make further attack more likely’ (p.104)? Time will tell.

Thus, it is clear that China does not have the great deradicalisation tool it claims to have. It is not really protecting its public from a threat; it is waging an open war against a threat it believes will turn radical and it is doing so by defying basic human rights in the name of security. This, of course, is not to say that deradicalisation strategies do not work. But it should be understood that this global obsession with fighting radicalisation could easily backfire. It could even create, rather than resolve, problems. Are we ready to deal with the consequences?

1 Comment

Important issue. Worth to note first:

A complaint has been lodged to the ICC. Here:

https://east-turkistan.net/press-release-uyghur-genocide-and-crimes-against-humanity-credible-evidence-submitted-to-icc-for-the-first-time-asking-for-investigation-of-chinese-officials/

Second, beyond unbelievable complications, fundamental method, must be, to distinguish, between, the religion itself on one hand, and, on the other, those individuals, deviating and twisting its interpretation. In such manner, at least, seemingly, good faith, political correctness, fairness, are kept, without causing radicalization of the rest of the group,or, nurturing hatred towards innocent people.

That is what has been done, by G. Bush, after the twin towers attack. One of the first things he did, was to visit a mosque, and declaring that:

"Islam is Peace"

Here:

https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2001/09/20010917-11.html

Thanks

Add a comment