Lawyers’ experiences with remote justice

COVID-19 has spurred on the use of remote justice. What do Dutch lawyers think of video trials? Responses vary widely. Video trials are here to stay, but cannot fully replace physical trials.

Courts locked down: welcome remote justice

On 15 March 2020, the Council for the Judiciary in the Netherlands announced that due to the COVID-19 outbreak, district courts, courts of appeal, and special tribunals would close from 17 March onwards. Urgent matters did continue, but behind closed doors. In the following months, a lot of hard work was done to make court buildings COVID-proof and to speed up the implementation and use of videoconferencing in the justice system, including the criminal courts. On 11 May, the closure of the courts was partly lifted, in part thanks to the use of telephones and videoconferencing. Now a mix of types of court hearing is used: some litigants are physically present in the courtroom; some join the court hearing remotely, by video or telephone connection; and some cases are handled by written proceedings.

Dutch courts have already been experimenting with videoconferencing since 2000. Contact with a lawyer, interpreter or judge could already take place in real-time via a video connection before COVID-19: so-called videoconference, videoverhoren, telehoren or Video-Mediated Interpreting. Some pilots were also carried out. However, most court actors have no experience with these types of court hearings. The use of videoconference in court has been accelerated and upscaled due to the nationwide measures to contain the spread of the coronavirus. What do court actors think of this and what are their experiences? Do they like it? What problems do they encounter? Is a fair trial guaranteed? And is remote justice here to stay?

The research

To explore these questions, we studied the experiences of lawyers with remote justice and what they think of it. In cooperation with Advocatenblad and the research agency Tangram, and thanks to a small grant from the Erasmus Initiative ‘Dynamics of Inclusive Prosperity’

and the Department of Criminology, we invited lawyers to fill out our online questionnaire. 485 lawyers responded and participated in our study. We present some of our main findings below. Sabine Droogleever Fortuyn has provided a more complete report of the findings here in the Advocatenblad.

Satisfaction with video hearings

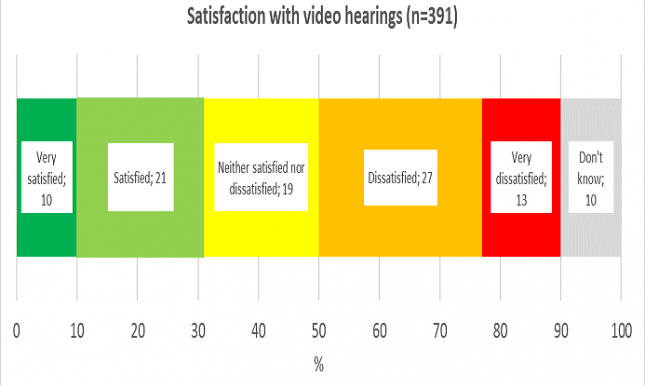

Our findings reveal great differences, both in experiences with remote justice and in appreciation. 75% had experience with trial by a video connection. The appraisal of these video hearings varied widely: more than 30% of participants were satisfied or very satisfied, 19% were neutral and 40% were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied (see Figure 1). Criminal lawyers were dissatisfied more often with video hearings than other lawyers.

Disadvantages of video hearings

Almost a quarter of the lawyers were dissatisfied with the voice they had in deciding on the type of hearing and in the scheduling of the video court sessions. And close to a third were dissatisfied due to issues with technology, such as bad connections, bad sound, or a failure to capture all parties on screen. Another reason for dissatisfaction was the 45-minute time limit for the court hearing that was set by prisons.

Further, many lawyers pointed out that remote justice does not leave enough room for emotions and they complain about the difficulties they encounter when they want to look at case files together with their client. They also point out that non-verbal communication is less apparent in video hearings and that clients report that they have less trust in the judiciary.

60% of the participating lawyers agreed that video hearings cannot meet the requirements of public access to court hearings and of transparency of justice. 35% believes that video justice is detrimental to legitimacy in relation to sentencing. Criminal lawyers were more critical about the impact of video hearings on the right to a fair trial than lawyers from other fields of law.

Benefits of video hearings

However, video hearings also have their upsides. Reported benefits are that remote justice saves time and money. Lawyers, for example, are no longer required to travel to the courtroom. Less time is spent waiting for the court session to start. And importantly, having a video hearing is better than having no hearing at all.

Is remote justice here to stay?

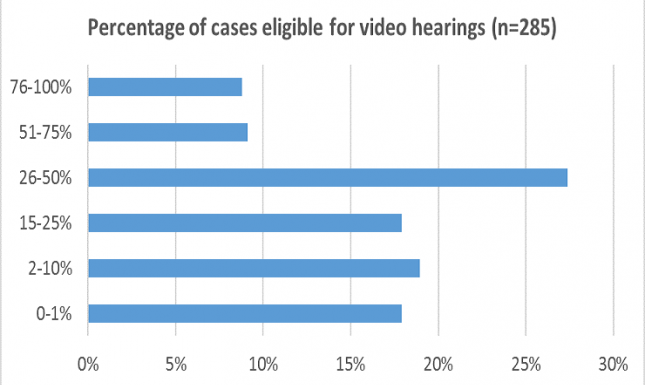

Video hearings have their disadvantages and benefits. But in the short time that courts have had to deal with remote justice on this scale, it already seems that it is here to stay. We asked the lawyers what percentage of their own cases would be eligible for video hearings. Here, again, the findings vary widely: 18% thinks at most 1% of their cases is suited for video hearings, and another 18% thinks more than half their cases could be dealt with by video hearings (see Figure 2).

This figure also shows that there are many cases that are considered unfit for video hearings. These include complex cases and cases involving strong emotions or vulnerable litigants. So we believe that video hearings are here to stay. That said, remote justice can never fully replace physical courtroom hearings. In some cases, you really need to be able to look each other in the eye without the diminishing two-dimensional effect of a screen.

These are the initial findings of our study. More in-depth analyses of the findings will follow.

1 Comment

Important issue these days. So, It is twice mentioned, I quote:

"Criminal lawyers were more critical about the impact of video hearings on the right to a fair trial than lawyers from other fields of law."

And:

"Criminal lawyers were dissatisfied more often with video hearings than other lawyers."

So, should we connect the dots, and assert that, if, I quote:

".... there are many cases that are considered unfit for video hearings. These include complex cases and cases involving strong emotions or vulnerable litigants "

Then, that is why criminal lawyers are dissatisfied ? At least, the issue of emotions seems right. Yet, Complexity, this is too complex.

Thanks

Add a comment