Meijers, Scholten and hazing violence

Debates on abolishing hazing are as old as the student corpora. In 1897, Eduard Meijers had a rough time entering the Amsterdam Student Corps, while abactis Paul Scholten tried to reform Corps law.

The festive opening of the academic year 2021-2022 in the Netherlands was unfortunately overshadowed by incidents of harassment during the hazing (ontgroening) of first-year students. Student associations keep working on codes of conduct or, like the Amsterdam Student Corps, are trying to abolish hazing rituals altogether.

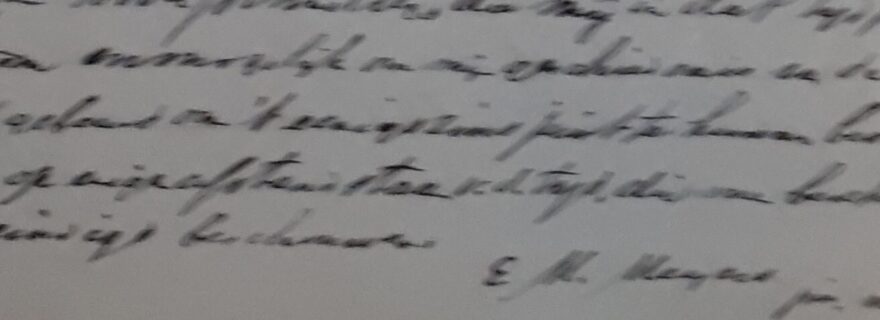

A rediscovered autobiographic paper written by Eduard Meijers (1880-1954) illustrates that this is nothing new under the sun. Written as a 17-year-old law student at the University of Amsterdam, this rare document also refers to his life-long friendship with Paul Scholten (1875-1946), a well-known member of the student Senate at the same university. Later becoming professors of civil law, both left strong personal imprints on the legal development of the Netherlands in the 20th Century. [1]

A biased autobiography

‘After (the exams) I was given the occasion to make a trip by foot through Luxembourg and surroundings. A trip by foot it was, as use was made of the feet as long as possible, so that in the end a blister appeared on every toe – anyway it was good training for someone who was about to go hazing and who lives half an hour outside the old city. Returning after a few weeks, time was spent helping the feet and the rest of the body recover a bit. But soon the holidays came to an end and the hazing period came into view …’

Like other aspirant members of the Amsterdam Student Corps, Eduard Maurits Meijers wrote his youth memories on 17 October 1897, at the end of the hazing weeks. As a biographical source, the story is intentionally biased, as the ‘greens’ were supposed to belittle their former lives. However, the document offers valuable insights into the subsequent periods of Meijers’ early youth, his years at primary and secondary school , and his expectations of student life:

‘.. and herewith I have arrived in the transition time until the fourth period. Still, this time is not ended, still I am waiting for the magic formulas, that will bring me into that period.' [2]

Hazing started on 27 September 1897, when Eduard made his way in the Odéon building in Amsterdam, ‘through a crowd of roaring and raging members, grasping roughly around to take away the groenenboekjes (‘greens’ booklets), containing matters upon which their suffering and struggling would depend’. Afterwards, the ‘greens’ were taken on an obligatory round of the disputen (fraternities) and associations of the Corps, and ‘received with donderjolen’ (‘jolly thunderings’) in order ‘to convince them of their nothingness’. These rough beer parties were part and parcel of the ballotage procedure, ‘with thorny demands and questions to gauge their character’. [3]

Eduard showed no visible interest in the fraternities, or maybe he could not afford the high costs of the obligatory beer parties, luxurious dinners and social events, on top of the membership fees. Unlike most Corps members, who had their rooms in the old city, he came from a modest middle-class family, still living with his parents at Linnaeusstraat 29 in the eastern district of Amsterdam. Father Isidor Meijers, a physician and former Marine health officer, was well-to-do but needed to be cautious with money. He had to finance the studies of his four sons Marinus (medicine), Albert (civil engineering), Eduard (law) and Gerard (civil engineering). The younger daughter Clara, attending ‘Higher Civil School’ (HBS), was not supposed to pursue further study. [4]

Eduard was a sportsman, as his future student Rudolph Cleveringa would recall: ‘he was a good gymnast, swimmer, ice skater and rower’. [5] After taking part in the ‘greens’ rowing contest, he was admitted to the student rowing association Nereus. Here, ‘greens’ were smeared with paint or, as happened to Eduard, forcefully pushed into the Amstel river. [6]

As a passionate chess player, he was also admitted to the student chess society P.H.I.L.I.D.O.R., named after grandmaster Philip Philidor. In order to distinguish themselves from chess clubs of ordinary people, the students had fabricated the Latin slogan Pete Hostem, Insta Latronibus, Inermis Deme, Obtege Reginam (‘Seek the enemy, advance upon the robbers, take away those not covered, protect the Queen’). However, they created a more sober atmosphere and actively took part in the national chess culture, introducing new forms such as mass competitions and correspondence chess. From 1899-1900 Eduard served as quaestor (treasurer) of the club. In the same year, he met the younger fellow law student Julius van Oven, who shared his love of the ‘noble game’. [7]

Aristocrats versus democrats

On 17 October, after a last ‘full outburst of despotism’, Eduard was registered as Corps member, followed the next day by a rijjool (‘jolly riding’) in wagons decorated with flowers and autumn leaves, the coachmen dressed up as bears. But the festive dinner ended in a fist fight between the most fanatic factions in the Corps, conservative ‘aristocrats’ and reformist ‘democrats’, who were deeply divided over hazing. In this overheated atmosphere, Eduard was impressed by the personality of 22-year-old law student Paul Scholten, the abactis (secretary) of the Corps. He was a scion of a patrician family in the old city and an active member of the elite literary dispute V.O.N.D.E.L., but remained modest, not displaying any studentikoos (pretentious student) behaviour.

‘During his time as a student he was, although never studentikoos, a popular student, chosen suo anno as abactis of the student Senate. He did not do any sports. He had something shy about him, so that one could recognise him already from the soft ring of at the front door. One did not call him Paul but Paultje (‘little Paul’). However, the same student, never seeking the spotlight, could suddenly become inflamed, when an opinion was upheld that he principally considered wrong; ... on the outside never dominant or hurting, and speaking a bit artificially, but on the inside of great decisiveness and strength.’ [8]

Serving as abactis in 1897, the jubilee year of Amsterdam University, ‘Paultje’ had helped organise the festivities, culminating in a city tour of coaches with corpora from other universities, a musique pavilion and a flower parade in the Vondelpark, well attended by the Amsterdam public. An innovation was the participation of ladies in these activities, which helped, as a newspaper observed, ‘prevent partying young men, as was usual at other similar occasions, pouring themselves full of fabulous quantities of alcohol and annoying people with drunken scenes’. The Senate expressed its gratitude for the good cooperation with the city police, donating Fl. 100 to the Police Fund charity. But Paultje also had to deal with many dozens of cancellations of Corps membership and complaints about hazing as ‘a series of cowardly amusements’.

In the Senate, Paultje waged an ongoing fight against inequality in Corps law, arguing that students, including Senate members and ‘greens’, should have the same rights and obligations. In long discussions about a new set of rules for the hazing period, he proposed the amendment: ‘The candidate members are not obliged to perform anything in public; it is forbidden for students to let them do anything indecent and to treat them with pawing behaviour ’. The majority in the Senate opted for a compromise set of rules that merely abolished the principle of ‘obligatory obedience’.

At the plenary meeting of 9 December 1897, Eduard witnessed the ‘decisiveness and strength’ of Paultje’s character. However, the moderate Senate proposal was outvoted by a 2/3 majority, although ‘democrats’ claimed they had observed massive fraud in vote counting. At the same plenary meeting, a new Senate was elected that preferred to end the discussion. One year later, after a new hazing scandal, the student rector commented: “For just a few days, the older members make use of their right to torment and taunt, but then it stops.” [9]

Flame of justice

Eduard Meijers and Paul Scholten differed in age by more than four years and apparently they did not meet often at Corps activities, as one liked sports and the other did not. Their friendship and professional affinity is likely to have grown at the law faculty, inspired by Professor of civil law Johannes Houwing who, with other outstanding teachers, offered the ’magic formulas’ that 17-year-old Eduard had been waiting for. But we should not underrate the formative influence of the Corps on their characters. With the rapid growth of scientific specialisations in the late 19th century, universities entrusted their traditional task of moral education more and more to the student corpora.

How would Meijers and Scholten look upon the present hazing scandals? They would probably agree that legal rules are not enough, if these are not inspired by the ‘flame of justice’. [10]

Drs. Marten van Harten is preparing a historical biography of Professor E.M. Meijers as external promovendus at the Department of History of Leiden University.

0 Comments

Add a comment