The paradox of Dutch counterterrorism measures

It seems that the Dutch Counterterrorism Act has not contributed to government objectives. Does the Act limit threats to national security or does it threaten the foundations of Dutch society?

In 2017, the Dutch government announced the Wet bestuurlijke maatregelen terrorismebestrijding (Counterterrorism Interim Administrative Measures Act). This Act will expire after five years and its intention is to limit the risks to national security posed by individuals associated with terrorist activities or the support of such activities. The Act imposes extensive administrative control measures to reduce threats posed by jihadism: ‘a duty to report regularly to the police’; ‘restrict access to certain places and areas’; ‘restrict contact with specific people’; and ‘restrict the ability to travel outside the Schengen area.’ In the fight against terrorism, it is relevant today to reflect on the effectiveness and impact of this Act.

Fear created by fear

Since the 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon, the world has been increasingly concerned about terrorism. Ulrich Beck has described this as the ‘terrorist world risk society’. Following Beck’s thesis, described by Mythen and Walklate as well as Giddens, modern society is increasingly preoccupied with future risks because of the unintended and unforeseen growing shift from an industrial to a technologically advanced society. During this shift, human intervention has caused a transition in fear from external to manufactured risks. While anxiety for natural risks has faded away, Mythen and Walklate argue that modern society itself has created new risks. According to Beck, terrorist risks in particular cannot be delimited by institutional intervention and endanger greater potential harm with generated irreparable effects, causing a chaotic risk society with radical changes in politics and social distribution.

But is there a real terrorist threat to the Dutch national security?

The Dutch government considers the jihadism movement to be the major threat to national security. Based on various information sources, the Netherlands is working with a system of threat levels that indicate the probability of a terrorist attack. Currently, the threat level continues to be 3 out of a possible 5; a terrorist attack in the Netherlands is a real possibility.

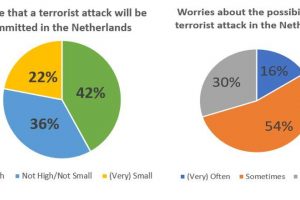

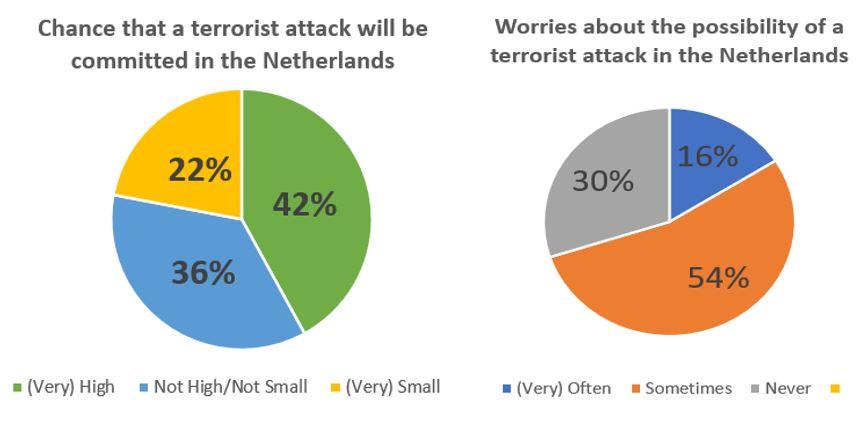

In 2017, a report by Statistics Netherlands (CBS) on public opinion regarding terrorism disclosed that 70% of Dutch citizens is worried about the possibility of a terrorist attack. Nevertheless, only 42% think that there is actually a high chance that a terrorist attack will be committed.

Effects of globalisation

Globalisation has massive impact on our modern risk society and Jarvis refers to the speedup movement and exchanges all over the world. As Halliday explains, globalisation has two inter-related elements: (1) the opening of borders to increasing flows of people, goods, services, and all other forms of exchange; and (2) the changes in politics and mechanisms at national and international level that contribute to such flows. This process affects all States and social classes because globalisation does not recognise boundaries. The downside of globalisation facilitates new and unforeseen risks and anxieties.

According to Van der Woude, many events in western society have contributed to the increasing anxiety in the Netherlands. A few examples are the murder of Theo van Gogh (Amsterdam, 2004); airport shootings (Germany, 2011); shooting at Jewish Museum (Brussels, 2014); Charlie Hebdo shootings (Paris, 2015); suicide attack (Brussels, 2016); and tram shooting (Utrecht, 2019). More examples can be found here. The short timeframe in which all these events occurred has had a significant effect on the rising feeling of insecurity in the Netherlands.

Thus, modern society is going through a growing shift where it is being forced to deal with unpredictable and new risks. Additionally, these risks remain constant globally, and could therefore harm people all around the world. Giddens argued that modern society lives in constant fear because ‘we don’t and we can’t know’ the diversity of new risks.

So, who can we hold responsible?

Pre-crime response

To rule out future risks and threats by terrorists, McCulloch and Pickering argue that all politicians and institutions are being forced to create pre-emptive security measures. However, risk and threat anticipation consolidates tendencies in traditional criminal justice systems by focusing on crimes not yet committed. Modern criminal justice is thus focused on pre-crime with ‘the aim to identify threats and make interventions before crimes take place’.

The Dutch Counterterrorism Act is an excellent example of pre-crime measures that are intended to limit the threats posed by jihadism. To be more specific, the Act embraces three major objectives: ‘to protect democracy and the rule of law, to weaken the jihadist movement and to remove the breeding ground for radicalisation'. By justifying the counterterrorism measures based on protecting national security, individuals can be subjected to widespread control measures and restrictions before actually committing crimes.

But is this an effective solution to limit terrorist threats?

An evaluation report published by the Dutch Research and Documentation Centre (WODC) in 2020 revealed that the counterterrorism measures have not contributed to the government’s objectives and that these measures have only been applied in a small number of cases. For instance, the measures did not contribute to deradicalisation, knowledge about individuals associated with terrorism, nor to a proper estimate of new risks and threats. Unfortunately, the measures have little added value in the fight against terrorism. Even more dramatically, interviews held by the WODC show that certain police officers, members of the judiciary and officials from municipalities argue that these measures can be counterproductive in practice and could even ‘trigger terrorist attacks’.

However, from a human rights perspective, the most problematic thing about this Act is the fact that executive authorities can interfere with individual rights without effective judicial control. According to the European Court of Human Rights’ ruling in Szabo and Vissy v. Hungary (2016), these measures authorised by executive authorities are ‘eminently political’ and ‘incapable of ensuring the requisite assessment of strict necessity with regard to the aims and means at stake’. This may cause a potential clash between national and supranational norms, and the Netherlands should take this into account, as Halliday and Zamboni argue. Moreover, the Act undermines individuals’ right to freedom of movement guaranteed in Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Conclusion

To conclude with the central paradox of Beck’s risk society applied to the Dutch Temporary Administrative Powers to Counter Terrorism Act: the Netherlands is trying to limit the manufactured threats and risks of jihadism by a set of far-reaching counterterrorism measures. However, by doing so the Netherlands is not contributing to its objectives, but is undermining human rights and even triggering new terrorist attacks. Unfortunately this Act is undermining the foundations of Dutch society, creating new and unforeseen threats.

0 Comments

Add a comment